Amazon Echo Rooting: Part 1

Update: You can view Ike Clinton’s paper that is mentioned in this article here. It is the basis for most of this research so far. There is also a Slack channel and wiki about this subject. The PCBs I ordered came in but I haven’t had time to solder the components on or test it out. A few people in the Slack channel have gotten their own code running on the Echo, so it is possible!

Introduction

I’ve been tentatively looking around for a root exploit or method for the Amazon Echo (not a referral link) since I got mine exactly a year ago. I love what it does and that it’s skills are being expanded every day by the Alexa Skills Kit, but I want to dig deeper into the code running on the device and possibly develop some lower level applications than what is allowed by the Alexa Skills Kit or add more music providers (I’m a Google Play Music user). A side effect of my endeavor into the Amazon Echo is being able to audit it for privacy. A few years ago, nobody would have been on board with putting a device specifically designed to listen to you 24/7 from a company like Amazon into their home. Now, the Echo is making appearances in homes across the country. I don’t personally believe the theories that Amazon is always listening (Wireshark strongly implies that they’re not), but I will be able to audit the software to make sure they aren’t.

I’ve come up with several possible ways to gain access to the Echo:

- Exploit vulnerable service: Embedded devices are notorious for running out of date software with serious security flaws. However, the Echo has very strict firewall rules that prevent access to most services that are running.

- Command injection: The primary user input of the Amazon Echo is the user’s voice. The Echo just uploads the audio data it records to Amazon and gets a response to relay, so it is extremely unlikely that we will be able to gain access to the Echo this way.

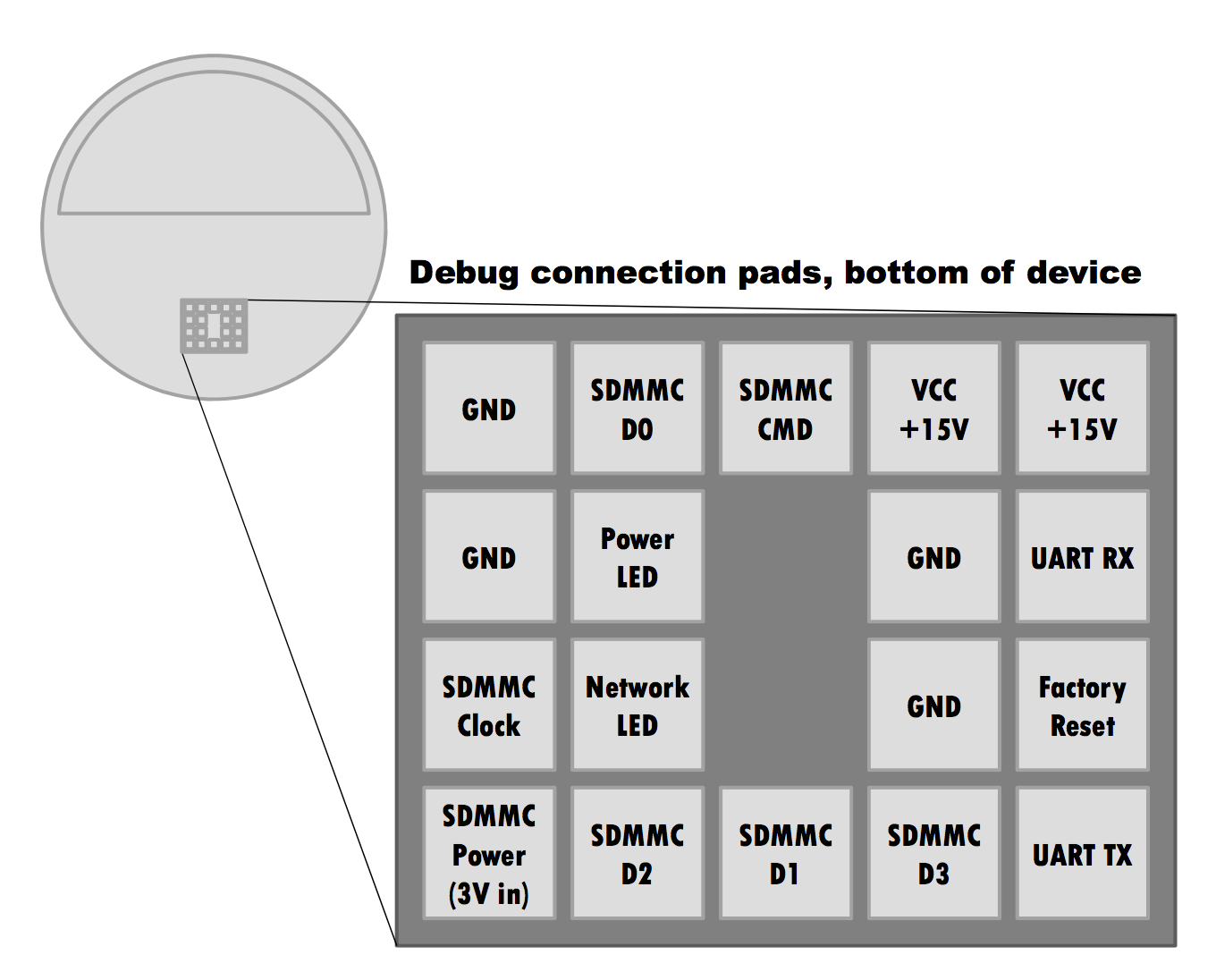

- Hardware: The Amazon echo has several debug pads on the bottom of the device that had an unknown function until recently. This is probably the most viable way to gain access to the device. I plan to use this method first, then look around inside the device for any other vulnerabilities.

Gathering Information

After connecting the Echo to my network and observing it’s traffic, I noticed that it downloaded updates in the clear. The Echo uses a modified version of the Debian Package file format with added support for signing of packages. I assume that the echo will not install packages that are not signed by the correct keys. The Echo downloads a package that contains a “manifest” from amzdigitaldownloads.edgesuite.net. The manifest is a list of all available packages.

While looking through the filesystem, I noticed a static network configuration for a USB Ethernet adapter. This is probably for internal testing at Amazon. We have seen this testing cradle with Ethernet connector in public during a demo of its integration with Vivint security. There are several other interesting bits of information like several references to the project’s original codename “doppler” and voice model data for using the word “Echo” as a wake word instead of “Alexa” or “Amazon.” There is also a firewall setup script that allows us to see which ports are open during normal operation and setup.

Thanks to a research project by Ike Clinton and an anonymous source, we now know the pinout of this test header. The Ethernet port was likely connected using SDIO on the SD card pins. There is also a UART console available on UART TX/UART RX at 115200 baud, but it does not accept any user input during the boot process. Attempts to halt or interrupt the U-Boot process were unsuccessful.

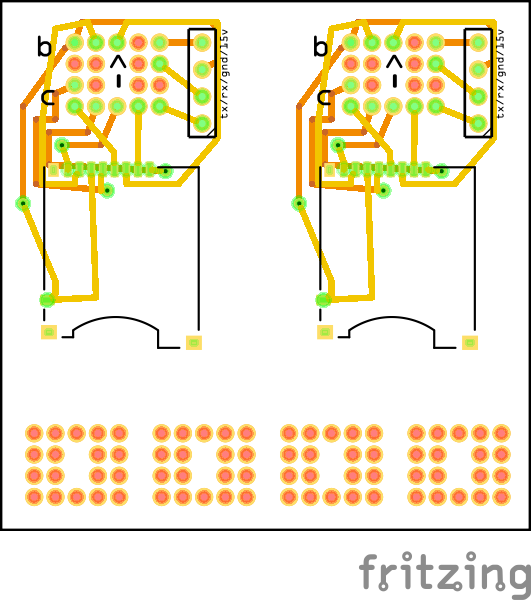

Analysis of the Echo’s bootloader code shows that it will attempt to boot from an SD card if one is connected to the pins on the debug header. The pads on this header are slightly smaller than 1x1mm square with a 2mm pitch. To avoid tearing pads off my Echo if I made a mistake and to make the process of connecting an SD card and UART header to an unmodified Echo easier, I attempted to create a 4×5 block with 2mm pin headers. I spent a few hours fiddling with melting the cheap plastic on the headers I had and decided to try to design my first breakout board to use with pogo pins.

The breakout board takes the 4×5 2mm header on the bottom of the Echo and converts it to a MicroSD socket and .1inch header that exposes UART TX, UART RX, GND, and +15V for power. I ordered 10 of these PCBs. When they come I’ll solder on all the components and write another post on creating a SD card that the Echo will boot off of. Hopefully from there I can edit some scripts on the Echo to enable a telnet server and punch a hole in the firewall to allow access to the running system.

The breakout board takes the 4×5 2mm header on the bottom of the Echo and converts it to a MicroSD socket and .1inch header that exposes UART TX, UART RX, GND, and +15V for power. I ordered 10 of these PCBs. When they come I’ll solder on all the components and write another post on creating a SD card that the Echo will boot off of. Hopefully from there I can edit some scripts on the Echo to enable a telnet server and punch a hole in the firewall to allow access to the running system.